SOME 60 YEARS LATER, MANY OF HIS UW FRATERNITY BROTHERS WILL ATTEND BUD SELIG'S INDUCTION INTO THE HALL OF FAME IN COOPERSTOWN.

Story by Tom Haudricourt, courtesy of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

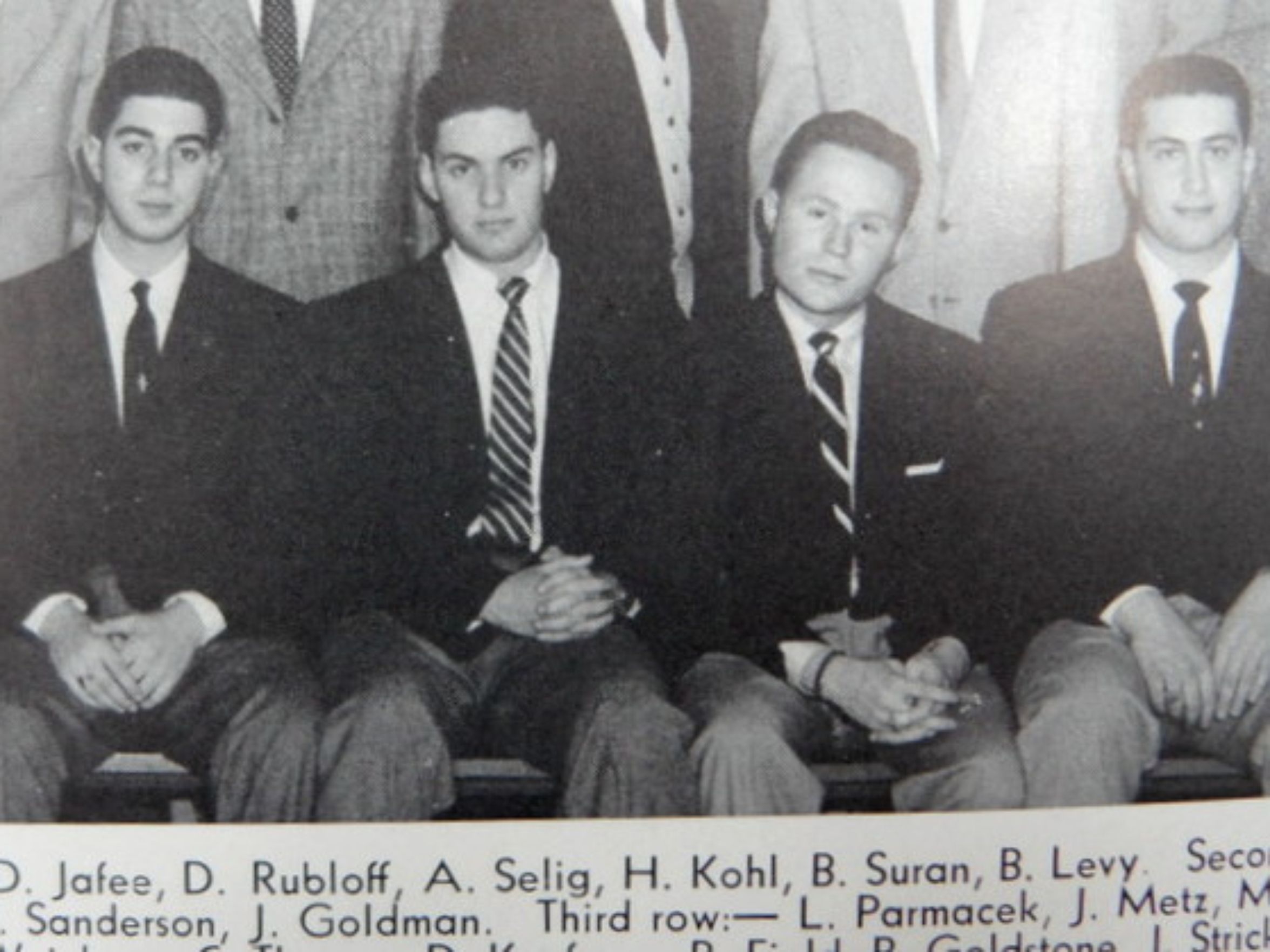

Photo: UW Digital Collections

When Bud Selig steps to the podium next Sunday in Cooperstown, N.Y., to deliver his acceptance speech during induction ceremonies for the Baseball Hall of Fame, there will be many familiar faces in what is expected to be an enormous crowd.

One group of men will be viewed with particular fondness by Selig, linked by a unique bond that has endured for more than a half century. Herb Kohl, Steve Marcus and Lewis Wolff will be joined by others who first met as members of Pi Lambda Phi fraternity at the University of Wisconsin in the mid to late 1950s.

“All of his associates and fraternity brothers, we feel we’re getting in (the Hall of Fame), too,” Wolff said. “We identify with Bud so much.”

By any measure of future success, the group of young men who gathered daily at the Pilam fraternity house was an extraordinary bunch. There were those who went on to become prominent attorneys, businessmen, physicians and leaders of men in their communities but it went far beyond that with some. And it all started with childhood friends Selig and Kohl, who grew up on the West side of Milwaukee and stayed together through every level of education.

“We grew up a half block from each other,” said Kohl, whose family lived on 51st Boulevard. “We went to Sherman School together, then Steuben Junior High and Washington High School. Then it was on to UW. We were very close, so it was no surprise we ended up in the same fraternity.”

It’s difficult to imagine a pair of college roommates going on to greater things than Selig and Kohl, each destined for individual greatness.

Kohl would serve in the Army Reserve before getting his professional career started in financial investing, then the family grocery and department store businesses before buying the Milwaukee Bucks and going on to serve 24 years as U.S. senator from Wisconsin. Not a bad life path.

Selig would return to Milwaukee to work in the family car business but had little interest in making that his livelihood. An avid baseball fan, he made it his mission to return Major League Baseball to his hometown after the Braves bolted for Atlanta in 1965. Selig led the group that founded the Milwaukee Brewers five years later and went on to become commissioner of baseball, serving a 22-year term that morphed from turbulent to transformational.

As if that weren’t enough, Selig was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in December and will be inducted with four others on his 83rd birthday, gaining immortality in the sport he loves so dearly.

Marcus arrived in Madison from Milwaukee a year after Selig and Kohl, and was new to both cities. Marcus was born in Minneapolis but spent parts of his childhood in Ripon and Oshkosh, where he went to high school before his family moved to Milwaukee. He, too, pledged Pi Lambda Phi, where he quickly noticed Selig’s affinity for baseball.

“That’s about all he thought about,” Marcus recalled. “We’d come back to the fraternity house, especially in the spring, and he always had a baseball game on. In those days, it was just radio. He knew what games were being played and how to find them.”

Like Selig and Kohl, Marcus would return to Milwaukee and become a huge success, joining the entertainment and hotel corporation founded by his father, Ben (Selig’s father also was named Ben). He is chairman of the board of the Marcus Corporation, which owns or manages 895 movie screens in eight states as well as 17 hotels, resorts and other properties in nine states, including the venerable Pfister Hotel downtown.

Wolff, who arrived at UW that same year from St. Louis, said Selig and Kohl were more focused as students than he was initially.

“We were in the fraternity together but they were in the library most of the time,” Wolff said. “I didn’t know where the library was until I was a junior.

“From the day I met Bud, I told him he was the 15th man picked on a nine-man team, but he never missed a fraternity or college game in any sport. He was always there rooting. He had an unbelievable passion, especially for baseball, for somebody who wasn’t that active physically in it.”

Wolff, 81, was destined to make his mark as a baseball owner as well. He first launched a career as a real estate mogul in the Bay Area of northern California and was credited with the redevelopment and revitalization of downtown San Jose. He joined an ownership group that purchased the Oakland Athletics in 2005 and remained a managing partner until selling his share of the club last November.

The fraternity success stories from those years went on and on. Frank Gimbel would become a dogged legal prosecutor before switching sides to criminal defense attorney in Milwaukee. Known in town as “Mr. Clout, he also served many years as chairman of the Wisconsin Center District.

Bill Grinker went to Harvard Law and landed in New York City, where he became a successful director and consultant to the small business community. Mel Pearl returned home to Chicago and became senior partner of a huge law firm.

Not exactly the bunch of losers that partied all day and night at Delta Tau Chi fraternity in the movie “Animal House.”

“It is unique,” said Kohl, 82, whose younger brother, Allen, also was a fraternity member. “A lot of the guys have gone on to have very successful lives. We’ve stayed in touch with each other. We’ve had several reunions of that fraternity over the years. A bunch of them have been in Milwaukee. It’s always good to see everyone.”

There will be another reunion of sorts in a week at Cooperstown. Wolff is making the 3,000-mile journey from California on his private jet, stopping in Phoenix to pick up fraternity brothers Don Sandler and Jim Metz.

“It will be a long jaunt but it will be worth it,” Wolff said. “I would not miss this, period.

“He still stays in touch with so many of us. People are just drawn to Bud. He really was a born leader. If you stamped out a list of leadership, Bud’s name would be at the top.”

Wolff watched Selig exercise his leadership skills in getting UW football player Charlie Thomas, an African-American running back who played behind Heisman Trophy winner Alan Ameche, in their mostly Jewish fraternity. This was years before the Civil Rights movement reached its peak, and Wolff said Thomas’ proposed membership “was a big deal in those days.”

“Bud and a few of us thought he’d be great for the fraternity but he had to be voted in,” Wolff recalled. “Some of the guys were not excited about it. I remember Bud saying, ‘We’re going to stay here in this meeting as long as it takes, even if it goes into the next day, to settle this in a fair way.’ And, so, Charlie eventually was voted in, and we loved him.”

Selig called that night “an interesting experience” but never considered it controversial to bring Thomas into the all-white fraternity. He and Thomas had become good friends, spending nights together in the library and stopping on the way back to their rooms to eat burgers at a joint they called “Greasy George’s.”

“He was a wonderful human being; I loved Charlie,” said Selig, who long has considered the seminal moment in major-league history to be Branch Rickey integrating the game with Jackie Robinson.

“The guys really liked him. It wasn’t because he was a football player. He later became superintendent of all the suburban Chicago schools. He was a remarkable guy.”

Many years later, when Wolff owned the Oakland A’s, he often watched Selig work a room in similar fashion as commissioner. Selig became the consummate consensus builder, cajoling, pleading and often pestering owners until they saw things his way and voted as he desired.

“He could be very persuasive,” Wolff said. “That’s what made him a successful commissioner.”

Selig’s fraternity brothers watched him use those same skills to lead the charge to get Miller Park built when the future of the Brewers in Milwaukee was at stake in the late ‘90s. Kohl said Selig had become accustomed to getting his way as far back as the sixth grade, when the two friends were captains of peewee baseball teams that advanced to the league championship game.

“We were both undefeated and playing for the championship on a Saturday morning,” Kohl said. “We get to the field and we start warming up, and we see this big, tall guy, well over 6 feet tall, come in and start warming up.

“I said, ‘Selig, who is this guy?’ He says, ‘Well, my regular pitcher, Freddie, couldn’t make it, so we got this guy.’ I said, ‘Why isn’t Freddie here?’ He said, ‘Freddie wouldn’t drink his orange juice so his mother wouldn’t let him come.’ We had a big fight about it and Selig said, ‘Quit your whining and let’s play ball.’

“So, I relented and we did and, sure enough, this guy pitches a no-hitter against us and we lost, 9-0. Selig wanted to win so badly, he puts this ringer out there. I never saw the kid again. He disappeared after the game.

“So, fast-forward all those years later and I turn on the television, and Bud Selig has just become the commissioner. He’s holding a big press conference and he says, “My No. 1 responsibility is to protect the integrity of the game.” I looked at the TV and said, ‘This is the guy who brought the ringer to win the game in the sixth grade.’”

Asked about Kohl's account of that day, Selig smiled broadly and said, "Herbie loves telling that story. The only problem is it's not true."

Kohl, of course, was speaking with mock contempt about Selig's integrity. As longtime owner of the Bucks before selling the club three years ago, he knew the importance of a commissioner who looks out for the sport, not his own reputation and popularity. Selig took an early hit over the labor war that led to the cancellation of the ’94 World Series and caught flak about overseeing the game during the so-called “Steroid Era” but Kohl said his childhood friend kept his eye on the ball.

“He devoted his life to baseball in various ways,” said Kohl, who also hopes to attend Selig’s induction ceremony. “First of all, getting the team back to Milwaukee. He was a great owner. Then he became commissioner and did a wonderful job.

“He saw the sport through some of the darkest days that weren’t his fault. He grew the game in every way and left it in outstanding shape. He has done great things in the game of baseball and wonderful things for Milwaukee. He deserves to be in the Hall of Fame and I’m very happy for him, and very proud of him.”

Kohl and Selig remained loyal not only to their fraternity buddies but also their alma mater through philanthropy. Kohl provided the lead gift for the Kohl Center athletic facility and founded the Herb Kohl Educational Foundation, which provides grants to students and teachers. Selig established the Allan H. Selig Chair in History in 2010, has helped create scholarships for students and serves as a guest lecturer in the history department.

More than 60 years after an extraordinary group of young men bonded at Pi Lambda Phi, inspired each other and set their course for future success, many will unite in Cooperstown in support of Selig. According to Marcus, 82, it is the least they can do to celebrate the ultimate achievement of one of their own.

“That says more about Buddy than it does about the rest of us,” said Marcus, who will make his first trip to Cooperstown. “When he became the commissioner, he could have put all of us in his rear-view mirror. And he never did that. He could have put Milwaukee in his rear-view mirror. He didn’t do that, either.

“He insisted on staying here and has been a major contributor to the community in many ways. It was amazing that he laid down that marker and it actually happened, and that we would be the home base of Major League Baseball. When you think about how difficult the beginning days of his commissionership were, it’s really amazing. But all he went through in getting problems straightened out, and how much patience and determination that took, it helps you understand why this is so well deserved.

“He’s very excited about it. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him quite as excited about anything, except maybe becoming a great grandfather.”

Selig is beyond thrilled that so many of his fraternity brothers will be on hand to witness his induction into the Hall of Fame. But, looking back at those years when a group of young men united before going on to great success, he said there was no way to forecast what lied ahead.

“We were just kids,” he said. “I can’t give you any logic for it. Herb and I were big sports fans. We talked about things that everybody talked about.

“Never in our wildest dreams did we imagine this would happen. It turned out to be an amazing group.”